How changing one word gave Are You My Boyfriend? a surprising new audience (and a stronger message)

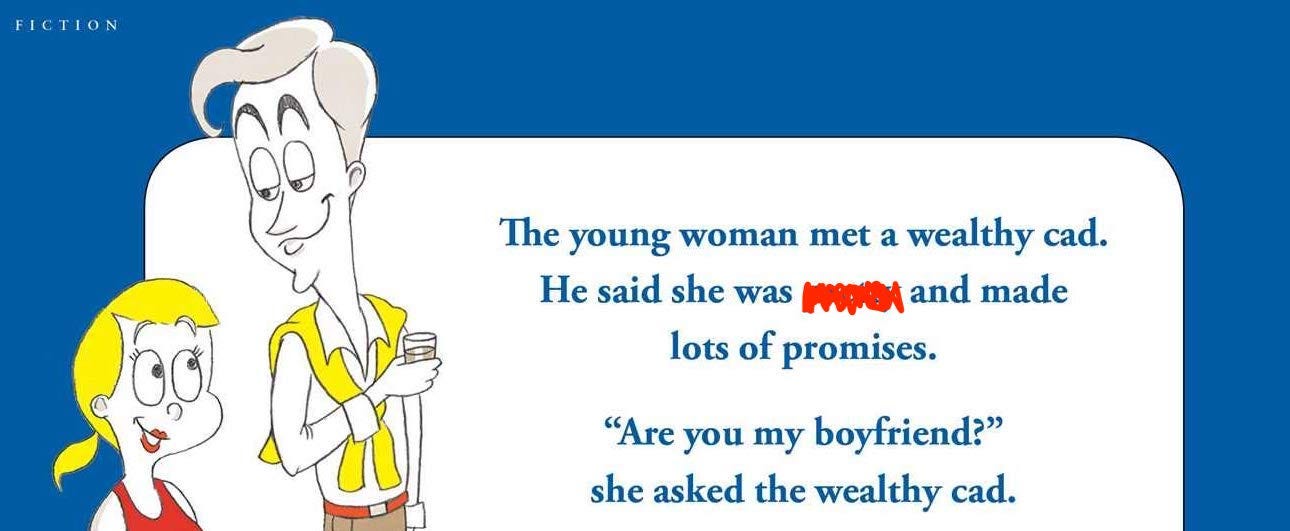

What do you notice about these two excerpts?:

The young woman met a wealthy cad. He said she was sexy and made lots of promises.

and

The young woman met a wealthy cad. He said she was pretty and made lots of promises.

Both are from the picture book Are You My Boyfriend?, and they each convey a similar meaning. But one is deemed inappropriate for children, and the other is embraced.

When I wrote Are You My Boyfriend?, I didn’t have children in mind. (Unless you count myself as an adult child, in which case, yes.)

But it turns out that kids love it. Adults buy it for other adults, and children are equally interested. Which actually makes sense. Sure, the book is ostensibly for women of a dating age, but it also has simple language, an engaging narrative, and lots of artwork.

As parents, my friends said they felt comfortable reading the book aloud to their impressionable young offspring. The themes (self-actualization, persistence, faith) were commendable, and visually, Are You My Boyfriend? made a seamless addition to a shelf of Dr. Seuss.

There was just one thing.

“You know the part where that guy says she’s sexy? I say pretty instead.”

That’s what my friend Claire told me. Her five-year-old son has been “reading” Are You My Boyfriend? since he was a baby.

This baby does not know what “sexy,” means, but he has already been told he is “pretty.”

At first she didn’t censor the language for her son, who didn’t understand what any of it meant anyway. But as he got older and AYMBF became a bedtime favorite, he’d ask questions about the illustrations, and then the words.

Claire knows she can’t protect her kids from sexualization — people told her that her baby boy was “gonna be a lady killer” before his first birthday. (This because her infant had long eyelashes.) Now that he’s five and his best friend is female, people tell him that his pal is “his girlfriend.” They make jokes about weddings.

Still, there’s no point in bringing up the word “sexy” during story time — especially when another word will do.

“Sexy just means that she feels pretty.”

That’s how Claire explained it, and why she now says “pretty” instead. I heard from other mothers who were making the same substitution, and I recognized there was a needless barrier of word choice.

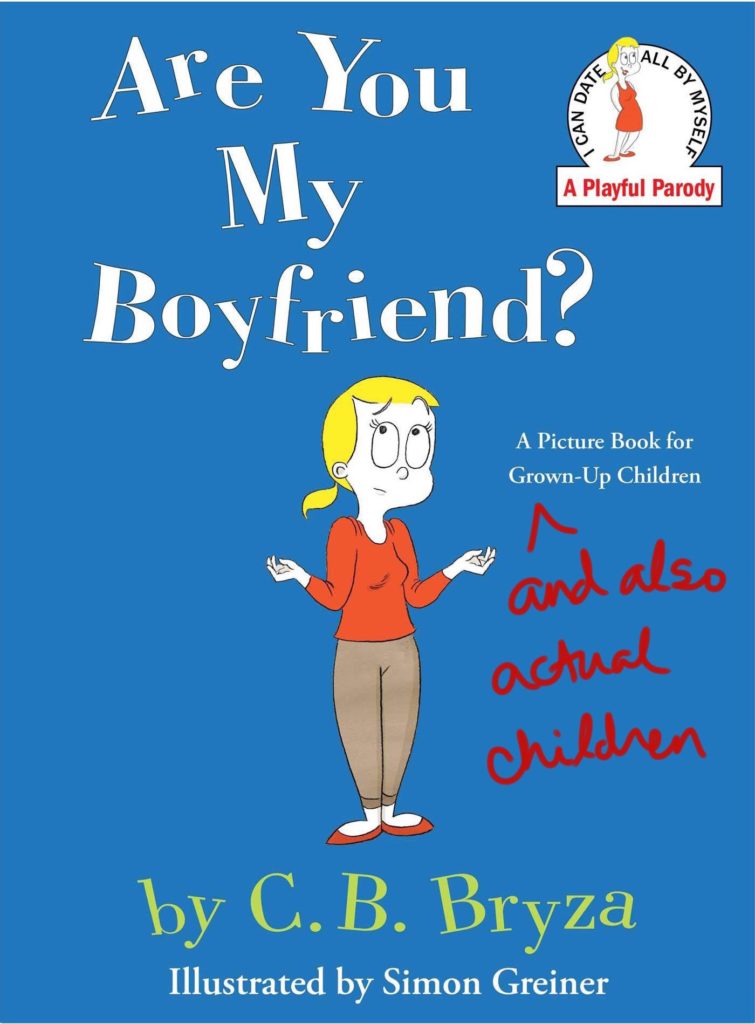

So when Simon & Schuster was preparing to print more copies of Are You My Boyfriend?, I asked if we could make a change.

Now AYMBF is more than a perennial addition to Galentine’s Day gift lists and post-breakup care packages. With the sole “grown-up” word replaced, the book is officially okay to share with children.

I’m happy about this, of course. Five years after its initial publication, I’m both humbled and thrilled to see the book reaching new readers.

But I’m also intrigued by how easy it was to change the language yet maintain the message.

Because in a way, saying “pretty” instead of “sexy” makes an even stronger point.

In the book, we learn that the main character is a young woman with a strong sense of self, a life purpose, and a heart full of love. She knows she does not require partnership to be a complete person, and she also knows that she desires partnership. So she sets out to find it.

And yet even though she is confident and self-possessed, she is vulnerable to the tactics of the first potential partner who speaks to her.

When he says she is sexy and makes her lots of promises, we can read her response (“Are you my boyfriend?”) as skeptical if we want to. Being told we are “sexy” is a red flag for many women.

But when he says she is pretty and makes lots of promises? “Pretty” is so much softer. It seems innocent—though it’s more like insidious. Now her same response reads as hopeful, maybe even naive.

Fortunately, the cad reveals his true character soon enough. (In addition to him proclaiming his emotional unavailability, we see he is a bad tipper.)

Yet the uncomfortable truth remains that most humans have been programmed to believe “pretty” is a desirable trait, particularly for females. And the associations of what it means to be pretty — to be approved of, accepted, wanted—are powerful.

So while we can sidestep the conversation around “sexy” with young kids, we shouldn’t ignore the impact of its gentler counterpart. Which is why I’m glad this book offers fair warning about the shortfalls of flattery.

I’m proud to be the book mama of a story that upholds important values. It means a lot to me that mothers from a wide range of religious and political backgrounds have told me they feel good sharing Are You My Boyfriend? with their children.

And since I also care about the adults that children become, I’m grateful we’re looking closely at language, at all ages.

Love > fear,

![]()

This post is also available on Medium.